Today is Mother’s Day, and I don’t think I could miss the opportunity to post about one of the best mothers in Torrey, Augustine’s mother Monica. She ranks high above the other mothers of Torrey, of which there are few, including Jocasta (who married her son Oedipus), Hera (who seeks the glory of herself and children as far as they are part of her in Ovid’s Metamorphosis), Penelope (mother of Telemachus and wife of Odysseus who fights off suites for several years, but never really says no), Gertrude (Hamlet’s mother who quickly marries his brother and does not mourn her lat husband’s death), Clytemnestra (wife of Agamemnon who kills him, starting a feud between her and her offspring), Mrs. Cruncher (who is devout in praying for her husband and son, despite being beaten for it), Mrs. Bennett (who’s just plain crazy), Mrs. Reed (the aunt who plays a tyrannical mother figure to Jane Eyre), and Dolly (Stiva’s wife in Anna K, who remains faithful to her husband even after he cheats on her). I’m not even going to discuss the church as mother, since that is a whole different topic. Continue reading

God

Spotting the Leopards

The leopard sneaks his way along many of the books in Torrey. He’s hard to spot because he shows up without any cause seemingly. Earlier I wrote a post on Ignatius, the God bearer, who died facing the “leopards of Rome”. A few weeks later in session we were discussing T. S. Eliot who again brought up the idea of leopards. I saw the small thread between the two and pointed out to my friend David. He helped me see what was really going on, so this post is dedicated to him.

Leopards show up in Ignatius’ letter to the Romans referring to the Roman guards bearing him to his martyrdom. While they get worse over time, he claims that they are making him more of a disciple of Christ, but he is only beginning to become a disciple. David points out that Ignatius’ goal is to replicate Christ in his physical suffering. He views these leopards as the instruments of God that will guide him towards his end. Continue reading

Battle of the Beasts (part 3)

In my last two posts I’ve discussed four of the biggest beasts in Torrey. In my first post I discussed Frankenstein’s monster and Melville’s Moby Dick. In my last post I looked at Spencer’s great dragon and Dante’s Satan, all the while comparing the beasts to one another. Finally I have arrived at the final beast. This beast is so great that it has beasts beneath him that he empowers. It is Satan, the Dragon of Revelation.

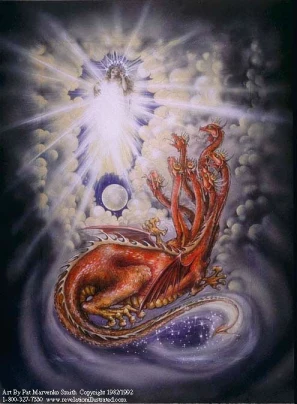

Revelation’s Dragon

In Revelation, John writes down the images and visions that Jesus shows him. After seeing many different things, he sees another sign.

And another sign appeared in heaven: behold, a great red dragon, with seven heads and ten horns, and on his heads seven diadems. His tail swept down a third of the stars of heaven and cast them to the earth. (Rev 12:3-4)

The great red dragon of revelation does not have long descriptors like those of the other monsters, but he is much greater. John sees him in heave and witnesses his magnitude. The dragon has seven heads (more than Dante’s three faces), ten horns, and seven diadems on each head. The diadems show that the beast is royally adorned and the horns denote power, more power than he has heads even. His tail is larger than Moby-Dick’s or Spencer’s dragon as it wipes out a third of the stars in the heavens and casts them down to earth (this may or may not be the angels, which still shows that he has power since he was able to deceive them to follow him).

The great red dragon of revelation does not have long descriptors like those of the other monsters, but he is much greater. John sees him in heave and witnesses his magnitude. The dragon has seven heads (more than Dante’s three faces), ten horns, and seven diadems on each head. The diadems show that the beast is royally adorned and the horns denote power, more power than he has heads even. His tail is larger than Moby-Dick’s or Spencer’s dragon as it wipes out a third of the stars in the heavens and casts them down to earth (this may or may not be the angels, which still shows that he has power since he was able to deceive them to follow him).

The vision continues:

Now war arose in heaven, Michael and his angels fighting against the dragon. And the dragon and his angels fought back, but he was defeated and there was no longer any place for them in heaven. And the great dragon was thrown down, that ancient serpent, who is called the devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world— he was thrown down to the earth, and his angels were thrown down with him. (Rev 12:7-10)

The dragon was in heaven and fought the great angel Michael. The dragon, who is revealed to be the serpent Satan, looses and is cast down out of heaven to the earth. But even here he is shown with power. He is called ancient and the deceiver of the whole world. How powerful does he have to be to deceive the whole world? Even ancient is a display of strength as he is not some young force. Even being cast down out of heaven, he has strength. Continue reading

To Infinity and Beyond: Dionysius on Being and Evil

It took most of my freshman year to understand Plato’s ideas of Being and Becoming. It was a shock to me when Pseudo Dionysius took it a step further. As soon as I started reading him I messaged an upper class man to try to understand what was going on. She helped me complete my understanding of Plato and helped me see further up into Dionysius’s thoughts.

In the opening pages of Pseudo Dionysius’s The Divine Names, he writes about God as beyond Being itself.

We must not dare to resort to words or conceptions concerning that hidden divinity which transcends being, apart from what the sacred scriptures have divinely revealed. Since the unknowing of what is beyond being is something above and beyond speech, mind, or being itself, one should ascribe to it an understanding beyond being. Continue reading

Plato like Play-Doh: Being and Becoming

Being and Becoming. What do these terms even mean for Plato? This was probably one of the most difficult ideas to wrap my mind around freshman year. I heard professors talking about it all the time, but I never could figure out what it meant. After thinking about it for a semester, I was finally able to figure it out.

Plato explains his system of existence in Timaeus. He breaks existence down into three categories: Being, becoming, and space. Continue reading

Aristotelian Virtue

What is virtue? How does one practice it? Does virtue measure actions or a person?

One of the primary authorities in Torrey on virtue is Aristotle who examines virtue in Nicomachean Ethics. Aristotle, a student of Plato, thought differently about virtues than Plato. Where Plato believed in forms of virtue, Aristotle believed in moderation.

Virtue

Aristotle describes virtue as “a mean between two vices, one of excess and one of deficiency” (II.9). This is a sort of moderation or temperance, where one aims at the middle to achieve the goal. Aristotle applies to all virtues such as courage, generosity, and magnanimity. If courage is the median, then a deficiency of it is called cowardliness and an excess of it is rashness (Book III). For generosity, the deficiency is stinginess and the excess is wastefulness (Book IV). For magnanimity (essentially the virtue of knowing your place in society in relation to honor, or greatness of soul) the deficiency is smallness of soul while the excess is vanity.

Aristotle describes virtue as “a mean between two vices, one of excess and one of deficiency” (II.9). This is a sort of moderation or temperance, where one aims at the middle to achieve the goal. Aristotle applies to all virtues such as courage, generosity, and magnanimity. If courage is the median, then a deficiency of it is called cowardliness and an excess of it is rashness (Book III). For generosity, the deficiency is stinginess and the excess is wastefulness (Book IV). For magnanimity (essentially the virtue of knowing your place in society in relation to honor, or greatness of soul) the deficiency is smallness of soul while the excess is vanity.

Magnanimity is Continue reading

The Smudge of Sin: Athanasius and Anselm

God expresses his beauty through creation. There is no doubt of the beauty of the lilies that do not toil or spin. One can only stand in awe when looking up at the night sky full of stars and galaxies. The complexities of even the smallest cells, molecules, atoms, and everything smaller show the immense detail of creation while the world, stars, and galaxies show the vastness of his power. Yet in all of creation, nothing is so unique as man who bears the image of God. He is God’s masterpiece of creation.

Yet something has happened. Anselm of Canterbury writes, “The human race, clearly his most precious piece of workmanship, has been completely ruined” (A, 269). Sin has contaminated the great masterpiece and ruined it.

Athanasius and Anselm both refer to sin as a smudge on the masterpiece of God.

Athanasius focuses on the incarnation in his work so aptly named On the Incarnation. He delves into the purposes of the incarnation and why it was necessary. As he talks about man’s redemption, he compares it to an artist and an old portrait. Continue reading

Athanasius focuses on the incarnation in his work so aptly named On the Incarnation. He delves into the purposes of the incarnation and why it was necessary. As he talks about man’s redemption, he compares it to an artist and an old portrait. Continue reading

Friendship: Aristotle and Cicero

Friendship. Everyone needs it, but not everyone has it, much less good friendship. Why is friendship so important? What makes us friends with some people and not others? What is friendship anyways, much less good friendship? I don’t claim to be an expert in friendship, I’ve made plenty of mistakes. But two much smarter men have thought about it before me: Aristotle followed by Cicero.

Aristotle

Aristotle defines friendship as two people wishing for the goodwill of the other with them both being aware of it. If only one wishes goodwill towards the other without reciprocation it is not friendship. Similarly if only one wishes goodwill for the other and the other does not know it, there is no friendship. Of those relationships that constitute friendship, there are three categories: utility, pleasure, and virtue. Utility and pleasure friendships are very similar. Aristotle writes, “Those who love for utility or pleasure, then, are fond of a friend because of what is good or pleasant for themselves, not insofar as the beloved is who he is, but insofar as he is useful or pleasant” (Nichomachean Ethics, VIII.3). These friends are only friends because they have something external to them that fulfills the needs of the other. A rich man is a utility friend to a poor one, a witty friend gives pleasure to one who enjoys wit. These friendships do not enjoy the person in and of themselves, but only so far as they bring good to the lover. The youth tend to make pleasure friends because they are driven by their (erotic) passions, while the elder tend to make utility friends as they seek their own advantage in friendship.

Aristotle defines friendship as two people wishing for the goodwill of the other with them both being aware of it. If only one wishes goodwill towards the other without reciprocation it is not friendship. Similarly if only one wishes goodwill for the other and the other does not know it, there is no friendship. Of those relationships that constitute friendship, there are three categories: utility, pleasure, and virtue. Utility and pleasure friendships are very similar. Aristotle writes, “Those who love for utility or pleasure, then, are fond of a friend because of what is good or pleasant for themselves, not insofar as the beloved is who he is, but insofar as he is useful or pleasant” (Nichomachean Ethics, VIII.3). These friends are only friends because they have something external to them that fulfills the needs of the other. A rich man is a utility friend to a poor one, a witty friend gives pleasure to one who enjoys wit. These friendships do not enjoy the person in and of themselves, but only so far as they bring good to the lover. The youth tend to make pleasure friends because they are driven by their (erotic) passions, while the elder tend to make utility friends as they seek their own advantage in friendship.

The third type of friendship is for Continue reading

Bishops, Presbyters, and Deacons, Oh My -Ignatius

Bishops, presbyters, deacons. To many of us these words are associated with the Roman Catholic Church, inciting ideas of legalism, corruption, and strange doctrines. While I’m not here to defend Roman Catholicism, I do think it is unwise to jump to such conclusions. The ideas of Bishops, presbyters, and deacons come from the early church fathers, those who came directly after the apostles. One of these, St. Ignatius of Antioch, wrote to many churches on the importance of bishops and obeying them.

Saint Ignatius

Ignatius of Antioch, the name sake of my Torrey group, lived during the first century and was bishop of Antioch. It is said that he was the third bishop of the church, following St. Peter and St. Evodius. Scholars agree that he was likely a disciple of Peter and that Peter himself appointed him to this position. Ignatius does not appear in history till right before his death when he writes several letters to churches. He was imprisoned for some unknown reason and was led to Rome to be martyred.

His icon is easily distinguished as a man being eaten by two lions. I got to go to Rome this January where three of us from Ignatius got to see the church dedicated to him and where his remains were likely stored. He firmly believed that his martyrdom was for him to be found pure. Fox writes in his Book of Martyrs Continue reading

The Call to Love

The two authors we spend the most time discussing in Torrey are Plato and Augustine, and rightly so as both have deeply affected Western thought. Much of the development of theology, East and West, has come out of Augustine. I’ve already stressed the importance of Plato in an earlier post, which I’ll be referencing throughout this one.

Loving God

During my freshmen and sophomore years I wrote two papers on “The Call to Love” which took Plato and connected him to Christ’s command to love. While I am a better writer now, I believe the ideas in it have been the most important and fundamental to my spiritual growth as well as how I interact with the world around me. My thought forms around Plato’s tripartite soul and Christ’s command to love him and love others.

My theory originates from Mark 12:30. Continue reading